NYU Tandon researchers help bring the fossil record into the digital age with low-cost 3D scanning

PaleoScan assembled at Museu de Paleontologia Plácido Cidade Nuvens in Brazil

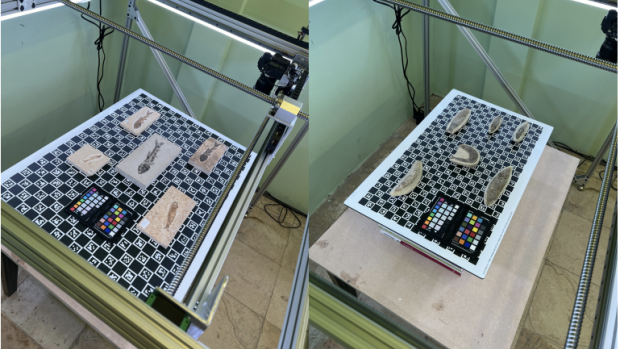

Inside Museu de Paleontologia Plácido Cidade Nuvens (MPPCN), a museum in rural northeastern Brazil, sits an unassuming piece of equipment that promises to digitize one of the world's most prized collections of ancient fossils.

PaleoScan, designed by NYU Tandon School of Engineering researchers as part of a collaboration between Brazilian paleontologists and American computer scientists, is a first-of-its-kind 3D fossil scanner that allows museum staff to rapidly and easily scan and digitally archive their vast fossil collection for global accessibility. The technology can democratize paleontology and archaeology in the process.

The research team presented a paper about PaleoScan’s development at ACM CHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems this month in Honolulu, Hawaii. View a video about PaleoScan.

"PaleoScan was created specifically to enable museums with limited resources to digitize vital fossil collections," said Cláudio Silva, NYU Tandon Institute Professor of Computer Science and Engineering and Co-Director of the Visualization and Data Analytics Research Center (VIDA), who led PaleoScan’s development. "This low-cost and easy-to-assemble technology delivers results that rival expensive CT scanners while working at a much faster pace. Affordability and high-volume output were paramount goals. We achieved them."

MPPCN’s 11,000 diverse and well-preserved fossils from Brazil’s Araripe Basin, one of the planet's most fossil-rich regions, hold immense scientific value.

Digitizing the museum's world-class collection has proved enormously challenging, however. Situated in the remote city of Santana do Cariri, transporting the fragile fossils over two hours to the nearest urban center risked damaging the specimens. Yet the museum’s lack of technologically-trained personnel, reliable internet, computing resources and funds for expensive scanning technology made on-site digitizing unviable.

"PaleoScan emerges as a powerful system for fossil investigation," said Naiara Cipriano Oliveira, visiting researcher at the MPPCN at Universidade Regional do Cariri in Brazil, who worked with Silva on installing the device and oversees the digitization of the collection. "Thousands of irreplaceable fossils will soon be readily available to scientists anywhere in the world, ensuring that evidence of ancient life is studied and preserved like never before."

PaleoScan is a fully self-contained system with innovative hardware and software components. At its core is a compact, automated camera rig that can slide along two axes above fossils placed on a calibrated surface. An intuitive touchscreen interface allows an operator to simply select which fossils to scan and the desired resolution.

The scanner's integrated camera (a mirrorless DSLR) then automatically captures a series of overlapping photos from different angles while LED lights ensure consistent illumination. This raw image data, stored on an SD card, is periodically uploaded to a cloud-based software pipeline developed at NYU Tandon.

The "PaleoDP" software processes the images using photogrammetry techniques to discern precise color, texture and geometry for each fossil down to sub-millimeter accuracy. Paleontologists can then easily annotate the 3D fossil data with metadata before it is added to an online database for other researchers to study remotely.

The PaleoScan device itself was assembled for less than $3,500, making it a low-cost solution for museums and fossil repositories to rapidly digitize their collections and make their specimens available for anyone to study.

In a pilot deployment last year, PaleoScan digitized more than 200 fossils at MPCCN in just weeks. At that rate, the entire specimen collection could be digitized and backed up in about a year.

High-resolution PaleoScan images revealed remnants of the ganoid scales of an exquisitely preserved fossil fish species, offering insights about its evolutionary biology and environment.

“The incredible preservation and abundance of these fossils from Brazil offer a rare opportunity to study the ecology of ancient environments. Now with PaleoScan, a scanner can come to the fossils rather than having fragile specimens sent to expensive scanners, allowing high-quality scans to be easily shared with the global scientific community,” said Akinobu Watanabe, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Anatomy at New York Institute of Technology and Research Associate at the American Museum of Natural History, who assisted NYU researchers in developing and deploying the device technology.

Looking ahead, scientists envision fleets of PaleoScan devices deploying to digitize neglected fossil collections globally, especially at underfunded museums and remote field sites lacking modern equipment. The portable, low-cost scanner could democratize access to the world’s archived fossil record for educators and researchers.

PaleoScan builds on Silva’s track record of developing new technologies for museums. He led an international team that worked with The Frick Collection to create ARIES - ARt Image Exploration Space, an interactive image manipulation system that enables the exploration and organization of fine digital art. The PaleoScan project has been partially supported through funding from the National Science Foundation in the U.S. and Fundação Cearense de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento (Funcap) in Brazil.

CHI '24: Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; May 2024; Article No.: 708; Pages 1–16 https://doi.org/10.1145/3613904.3642020