NYU Tandon researchers are developing AI-powered exoskeletons to enhance human mobility for everyone

New NSF-funded project builds on prior Nature research; aims to bring lightweight robotic devices from laboratory demonstrations to real-world use for older adults and stroke survivors

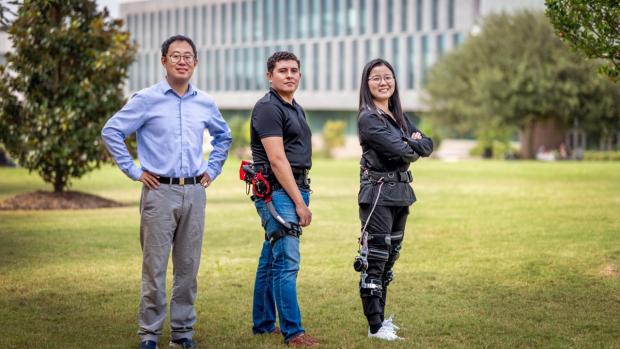

Hao Su (left) with his students Ivan Sanchez and Sainan Zhang modeling modular knee exoskeleton and hip exoskeleton. Photo credit: Hao Su

Approximately 31 million Americans experience mobility disabilities, with nearly 27% of older adults facing significant difficulty walking or climbing stairs. Yet current robotics solutions remain largely confined to research laboratories.

The fundamental problem, as Hao Su at NYU Tandon School of Engineering explains, is that existing exoskeletons "don't really understand humans’ intention." Most rehabilitation exoskeletons require 30 minutes or more to calibrate for each user and are uncomfortably bulky and heavy at around or more than 30 pounds, making people reluctant to wear them.

Su is leading a multi-university research team that is pursuing a solution through a recently awarded $3.6 million collaborative NSF Growing Convergence Research grant.

Building on a 2024 study Su and his colleagues published in Nature that proved exoskeletons can leverage deep reinforcement learning to train control policies entirely in computer simulation, the new project aims to take this technology from healthy-subject laboratory demonstrations into real-world community use for healthy people, older adults, and those with disabilities.

Ultimately, the team’s goal is to create affordable, lightweight exoskeletons that are intelligent enough to adapt to the needs of older adults and stroke survivors without requiring lengthy setup, while also being comfortable enough for daily use in their communities.

"This is truly an interdisciplinary endeavor. Our work involves mechatronics design, electrical engineering, computer science, rehabilitation medicine, and gerontology," explains Su, an associate professor of Biomedical Engineering.

The team's approach, which Su refers to as "physical AI," represents a fundamental shift from traditional methods. "Standard approaches require collecting extensive training data from 20 to 40 people for each study. In our Nature paper (see video below), we showed that our system requires no physical data collection for training. Instead, we utilized publicly available data and trained our system to accommodate a wide range of users. In this new project, we will use wearable sensors or cameras in smartphones to capture human movements to personalize control policies for each individual."

The approach uses a highly detailed virtual human body that simulates how hundreds of individual muscles and over 50 different joint movements work together. Using this virtual body, the team trains three AI systems that each handle different tasks: one learns natural human movement patterns, another determines which muscles should activate during movements, and a third decides what assistance the exoskeleton should provide in real-time.

The efficiency of this approach is remarkable. "The AI system that controls the exoskeleton only needs to train once for a few hours in the simulation. During this learning process, it gradually learned to generate effective assistance for walking, running, and stair climbing activities. In this new project, we will expand knowledge of assistive controllers to pathological gaits and more activities," Su explains.

The Nature study showed that people wearing the exoskeleton used 24.3% less energy during walking, 13.1% less during running, and 15.4% less during stair climbing. The mechatronics innovation of their robots is equally significant. Su's team has systematically reduced complexity and weight.

"We eliminated, for example, an expensive torque sensor by developing a new algorithm that estimates the same measurements using software instead of hardware. This makes the device lighter and much cheaper," Su explains. The team has built approximately 30 iterations of the device, each progressively lighter and more comfortable. The team’s version weighs about 6.6 pounds, as published in IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2025, compared to 30-pound tethered systems that confine users to laboratory treadmills.

The project’s vision extends beyond medical applications. "Our goal is what we call exoskeletons for everyone and everywhere,” said Su. “It's possible exoskeletons could be used, for example, for recreational activities like hiking. Or simply to make it easier for anyone to walk farther or longer distances in their daily lives."

The research team’s co-principal investigators are Xianlian Alex Zhou at New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT), Pamela Cacchione and Michelle Johnson at the University of Pennsylvania, Xiaoyue Ni at Duke University, and Bolei Zhou at UCLA.

Yan Y, Huang JS, Zhu J, Hou Z, Gao W, Lopez-Sanchez I, Srinivasan N, Srihari A, Su H. Compact and Foldable Hip Exoskeleton With High Torque Density Actuator for Walking and Stair-Climbing Assistance in Young and Elderly Adults. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics. 2025 Jul 8.