Huntington’s Disease is Neuroscience’s Clearest Test Case

Roy Maimon explains why the neurodegenerative disease is the ideal jumping off point for neuroscience research

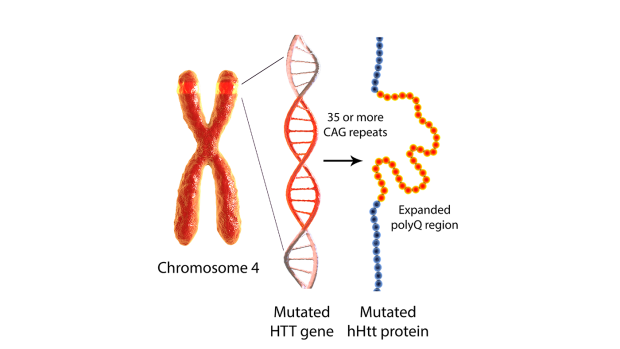

Mutant huntingtin, produced by a CAG repeat expansion in the HTT gene, is a central driver of Huntington’s disease pathogenesis.

Neuroscience rarely enjoys clean experiments. Most brain disorders are mosaics of risk genes, aging, lifestyle and chance that leave their origins obscured. Huntington’s disease (HD) is different. It begins with a single genetic expansion — a repeated stretch of DNA letters in the HTT gene — that is both measurable and decisive. If you inherit a sufficiently long repeat, you will develop the disease. That stark clarity makes HD scientifically invaluable.

That is the argument put forward by Roy Maimon in a new essay in Trends in Molecular Medicine. Maimon, Assistant Professor of Biomedical Engineering, is an expert in endogenous neural stem cells and their altered regenerative potential in brain diseases like HD. In the piece, he argues that HD’s clear cause and effects offer the ideal starting point to uncover parts of the brain, and the diseases that affect it, that are far less understood.

But it is not only the unique biological properties of HD that make it such a potentially productive topic — it’s the people too. “The HD world is unusually united,” Maimon writes. “It is among the few fields in biomedicine where patients, scientists, and clinicians share the same space. We meet families regularly. We see their courage and humor. We celebrate together and we grieve together.”

“It is this culture that makes HD research not just productive but deeply personal, too. You become part of something when you join this community that truly matters.”

The HTT mutation acts like a molecular clock. The longer the repeat, the earlier symptoms tend to appear. Decades before the first involuntary movement or subtle cognitive shift, a blood test can reveal who carries the expansion. Few neurological diseases offer such foresight. That predictability allows researchers to ask a question that is nearly impossible elsewhere: What happens if we intervene before neurons begin to die?

The brain changes in HD follow a surprisingly consistent pattern. Early damage centers on a deep brain structure called the striatum, which helps control movement and decision-making. Over time, connected regions of the cortex also become involved. Even within the striatum, certain neurons are especially vulnerable, while their neighbors remain relatively resilient. Why some cells are fragile and others hardy is a major puzzle — and HD offers a controlled setting to investigate it.

Because the genetic cause is so precise, HD has become a testing ground for cutting-edge therapies. Drugs called antisense oligonucleotides are designed to lower production of the harmful huntingtin protein. Gene therapies aim to deliver long-lasting genetic instructions that reduce or modify the faulty gene’s output. Other approaches target the DNA repair machinery thought to drive repeat expansion. Not every clinical trial has succeeded, but each has sharpened our understanding of how to measure brain changes, track biomarkers in blood and spinal fluid, and choose the best moment to intervene.

Researchers are also exploring ways to repair or replace damaged cells. The striatum lies near a region of the brain that can generate new neurons, at least in small numbers. In animal studies, boosting this process — or transplanting healthy cells — has shown promise in rebuilding parts of the damaged circuit. While such strategies remain experimental, HD provides a uniquely measurable proving ground: a known mutation, defined target cells and a predictable timeline.

“Every dollar invested in HD yields methods, models, and biomarkers that accelerate discoveries throughout the entire field,” Maimon writes. “For students, it's the quickest path to learning real translational neuroscience. For investors and funders, it’s the most efficient place to deploy resources: high-quality trials, engaged patients, measurable outcomes, and clear readthrough to other diseases. For scientists, it is a bridge between basic biology and the clinic.”

“New York University (NYU) is uniquely positioned to serve as a national hub for Huntington’s disease research”, Maimon adds. “The university bridges engineering, neuroscience, clinical medicine, and data science within a single ecosystem, allowing discoveries to move rapidly from molecular insight to patient-facing trials. With strong programs in gene therapy, RNA therapeutics, biomarker development, and computational modeling, NYU offers the interdisciplinary infrastructure required to tackle a disease that demands precision at every level. Equally important, its proximity to major clinical centers and patient communities enables sustained engagement with families living with HD, ensuring that translational efforts remain both scientifically rigorous and deeply human”.

Maimon, R. (2026). Huntington’s disease is the best investment in Neuroscience Today. Trends in Molecular Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2026.01.001