The Hidden Heroes of Modern Medicine

Why drug delivery systems are as critical as the drugs they carry

When we think about medical breakthroughs, our minds often jump to the discovery of powerful new drugs—life-saving antibiotics, revolutionary cancer therapies, or cutting-edge vaccines. But behind every effective treatment lies an equally crucial, and often overlooked, component: the drug delivery system. From simple tablets to sophisticated nanoparticles, how a drug reaches its target can be just as important as what the drug is designed to do.

In fact, the effectiveness, safety, and patient experience of any therapy often hinge on the delivery method. A perfectly engineered drug can be rendered useless—or even harmful—if it’s not delivered to the right place, at the right time, and in the right dose. Advances in delivery systems have opened the door to treatments once thought impossible, enabling controlled release, targeted action, and even the ability to cross complex biological barriers like the blood-brain barrier.

A perfectly engineered drug can be rendered useless—or even harmful—if it’s not delivered to the right place, at the right time, and in the right dose.

As medicine continues to evolve toward personalized and precision treatments, drug delivery technologies are stepping out of the shadows and into the spotlight. Here at NYU Tandon, our researchers are exploring why these unsung systems deserve as much recognition as the drugs themselves—and how they’re reshaping the future of healthcare.

Designing Smarter Drug Delivery with Protein-Based Materials

For decades, drug delivery has largely relied on chemical formulations and systemic therapies—methods that can be effective, but often scatter treatments throughout the body, causing toxic side effects and limiting their impact. Professor Jin Kim Monclare (CBE) believes a new generation of therapies will come not from chemicals alone, but from biologically inspired materials designed with the help of computational tools.

“Most Nobel Prize-winning work has focused on proteins like enzymes, therapeutic targets, or proteins and those involved in sustaining life through critical molecular interactions,” Montclare explains. “The next stage is to use those same approaches to design materials that can generate tissue, deliver therapeutics, and achieve much more targeted outcomes.”

A recent study from Montclare’s lab highlights this shift. The team engineered protein-based hydrogels that encapsulated the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin. When injected directly into tumors, these hydrogels shrank triple-negative breast cancers in animal models. Unlike traditional chemotherapy, which spreads throughout the body, the localized delivery kept the treatment concentrated where it was needed most.

What makes this approach distinctive is the way it was built. The hydrogel sequences were generated using computational design, allowing the team to predict which structures would assemble and function effectively. The material also revealed an unexpected property: it could be tracked in real time using ultrasound. “That visibility was completely new,” Montclare notes. “It means clinicians can not only deliver the drug locally but also monitor the material after injection, something that’s rarely possible with traditional biomaterials.”

Montclare frames the work as part of a broader push toward targeted, biocompatible therapies. Because the hydrogels are made of proteins—materials the body already recognizes—they are inherently biodegradable and less likely to trigger harmful immune reactions compared to synthetic polymers or metals. “We can solve the same types of problems everyone wants to solve in drug delivery,” Montclare says, “but with materials that are safer and more natural for the body.”

The lab’s work sits at the intersection of computational modeling, materials science, and medicine. By using design algorithms to narrow down which molecular sequences are most likely to succeed, Montclare and colleagues can accelerate the traditionally slow, trial-anderror process of biomaterials development. This efficiency could open the door to faster development of therapies not only for cancer, but also for regenerative medicine and other hard-to-treat conditions.

Jin Kim Montclare’s lab is exploring a new method for delivering the chemotherapy drug Doxorubicin.

Jin Kim Montclare’s lab is exploring a new method for delivering the chemotherapy drug Doxorubicin.

Montclare is quick to emphasize that her lab is not alone in this effort. At NYU Tandon, colleagues across multiple departments and initiatives are all advancing complementary work in drug delivery, cell therapies, and biomaterials. Together, they represent a growing ecosystem focused on reimagining what a “drug” can be.

That definition itself may be due for an update. Traditionally, drugs have meant chemicals in a pill or injection. But Montclare’s work— like related advances in electroceuticals and bioengineered carriers—suggests the future of medicine may include therapies that look less like small molecules and more like engineered biological systems.

Jin Kim Monclare

Jin Kim Monclare

"We’re on the cusp of really exciting science. By combining computation, biology, and engineering, we can design treatments that are not only more effective, but also safer and more personalized. That’s the future we’re building toward.”

Rethinking the Pill: Khalil Ramadi’s Vision for Smarter Drug Delivery

“The question of drug delivery is interesting,” says Assistant Professor Khalil Ramadi, a bioengineer at NYU Tandon and NYU Abu Dhabi, “because what is a drug?”

For Ramadi, much like Montclare, the question is an interesting one. He dedicates much of his research to delivering not only specialized chemicals like most people think of, but electrical signals that stimulate the nervous system.

For many years, swallowing a pill has been the simplest way to take medicine. But while convenient, oral drugs often face major hurdles: they must survive the harsh environment of the digestive tract, reach their target tissue, and avoid causing side effects elsewhere in the body. Ramadi is transforming a pill from a passive chemical carrier into an active therapeutic device.

Instead of relying solely on chemicals, these “electronic pills” can stimulate neurons and hormones in the gut using tiny embedded circuits. Because the gastrointestinal tract is lined with nerve cells and immune pathways, it offers a unique way to influence health without invasive surgery. “We’re trying to get the best of both worlds,” Ramadi explains. “Drugs are noninvasive but nonspecific; surgery is targeted but invasive. A smart pill could combine precision with ease.”

Khalil Ramadi

Khalil Ramadi

Ramadi’s group is also interested in leveraging electronic pills to tackle how to deliver cuttingedge therapies like biologics treatments orally. In collaboration with MIT and the University of Colorado, they are part of an ARPA-H initiative focused on revolutionizing the oral route, which explores both chemical and electrical therapies that could be administered through the gut. In this framework, even electricity can be thought of as a “drug”—a stimulus that nudges the body back toward health.

Ramadi’s curiosity also extends to the microbiome, the community of microbes that live along the digestive tract. Current methods rely on stool samples, which provide only a partial picture. His lab has designed sampling capsules inspired by coral reefs, whose porous structures naturally trap bacteria. These devices capture microbes from the upper intestine— where digestion and drug absorption happen— providing data that could one day guide more precise treatments.

For Ramadi, simplicity is key. His engineering philosophy emphasizes devices with few moving parts, fewer chances of failure, and maximum impact in real-world clinics. “If it’s going to be used, it has to be simple,” he says. By rethinking what a pill can do, his lab is opening new possibilities for drug delivery, where medicine could be as easy as swallowing a capsule, but far more powerful.

Engineering Tiny Devices to Guide Big Advances in Drug Delivery

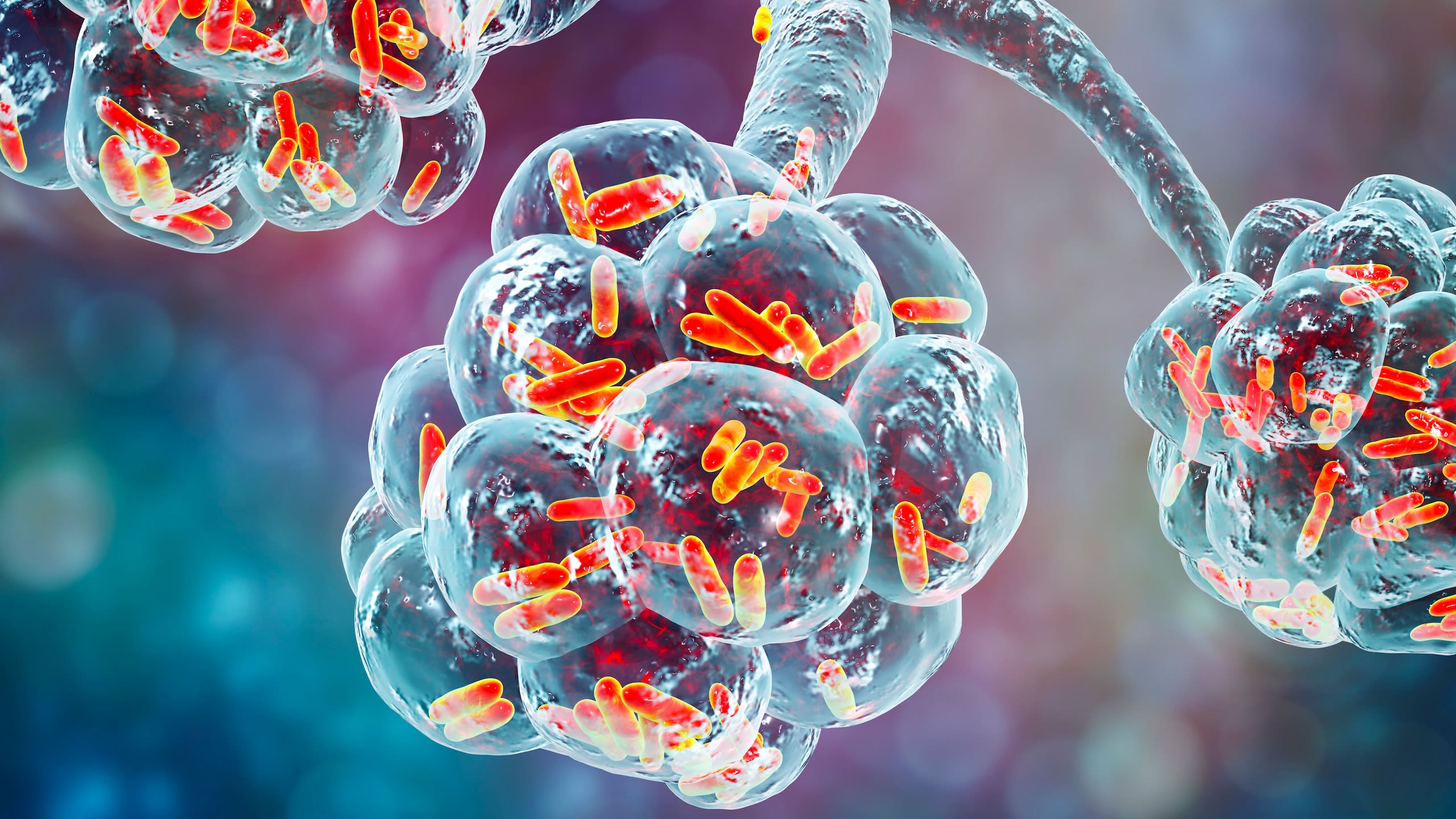

When most people picture mechanical engineering, they imagine engines, turbines, or large-scale machines. Katsuo Kurabayashi sees something different: miniature biochips that can guide life-saving drug treatments. Kurabayashi, chair of the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, develops microfluidic biosensors—tiny devices that integrate sensing materials and structures into channels thinner than a human hair. His team uses these devices to monitor how drugs, delivered by engineered nanoparticles, affect diseased tissue in real time.

One of the lab’s main targets is bacterial lung infections, which can trigger runaway inflammation and severe tissue damage. Working with collaborators at the University of Michigan, Kurabayashi’s group designed nanoparticles that carry drugs to infected lungs. The drugs block a specific enzyme that otherwise pushes immune cells into a harmful, tissue-damaging state. By shifting the immune response toward healing, this nanoparticle-based therapy significantly reduces lung injury in animal models.

Designing and manufacturing microfluidic chips requires mastery of fluid motion, device fabrication, and structural mechanics at extremely small scales.

The biosensors also play a crucial role in evaluating these therapies. Traditionally, tracking inflammatory biomarkers requires repeated, large-volume blood draws and costly immunoassays, burdensome to patients.

Kurabayashi’s devices solve this by enabling frequent monitoring from tiny samples, such as a pinprick from a mouse’s tail. “We can take many measurements over time and see exactly how quickly a treatment is working,” he explains. This continuous readout of pharmacodynamics how drugs act in the body—gives researchers a clearer picture of efficacy and safety.

Kurabayashi’s technology proved its value during the COVID-19 pandemic, when his team applied it to track biomarkers in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. The sensors helped physicians understand inflammatory patterns and tailor treatments for critically ill patients.

While chemistry and chemical engineering remain central to creating nanoparticles and drug formulations, Kurabayashi emphasizes the unique contribution of mechanical engineering. Designing and manufacturing microfluidic chips requires mastery of fluid motion, device fabrication, and structural mechanics at extremely small scales. “We’re not making engines, but we’re still making machines—machines that manipulate fluids and biochemical reactions to give us insights into disease and therapy,” he says.

Katsuo Kurabayashi

Katsuo Kurabayashi

Designing the Future of Drug Delivery

Assistant Professor Nathalie May Pinkerton has always been drawn to the intersection of chemistry, engineering, and medicine. As an undergraduate at MIT, she attended a lecture by Robert Langer, one of the pioneers of drug delivery, who described polymer-based wafers that released chemotherapy drugs directly into the brain after tumor removal. That talk crystallized something for Pinkerton: the materials she loved working with could be designed not just for elegance or efficiency, but to improve human health.

Today, as a faculty member in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Pinkerton directs a lab that designs nanomaterials to deliver drugs with precision 12 13 and reliability. Her team approaches the problem like chemical engineers through materials and process design. “We’re interested in developing new materials with properties that are useful in a biological setting,” she explains. “And just as important, we’re developing processes that allow us to make these materials at scale.”

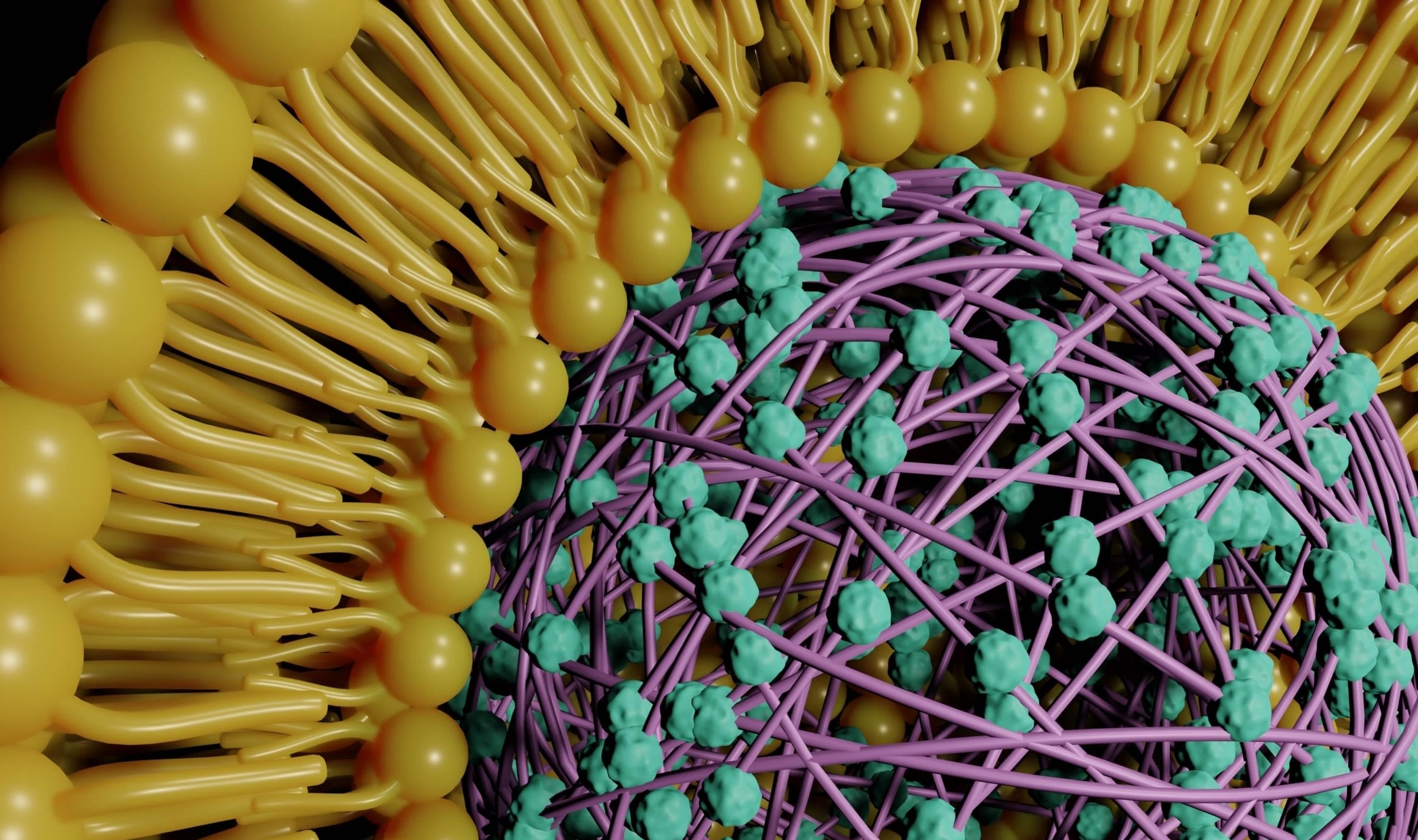

At the core of her research are polymeric nanoparticles—tiny engineered structures that can carry drugs to specific tissues. Unlike lipid nanoparticles, which gained widespread attention through COVID-19 vaccines, polymers offer an enormous range of chemical tunability. “Polymers give us a larger design space,” Pinkerton says. “We can tailor them for different therapeutic molecules and control how they behave in the body.”

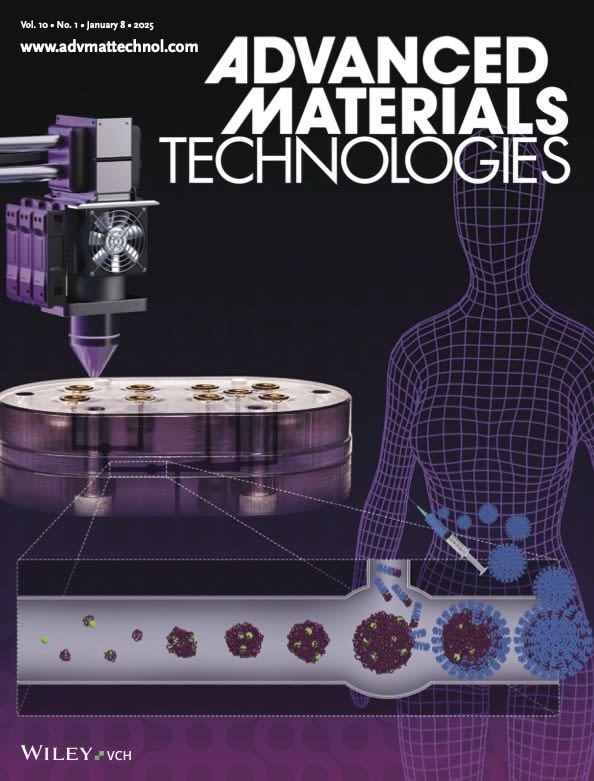

Pinkerton’s work featured on the cover of Advanced Materials Technologies (January 2025 Issue)

Her lab has focused on three major application areas: immuno-oncology, chronic pain, and blood clot treatment. In each case, the key is not just delivering drugs but doing so in a precise and controlled way. For example, in cancer immunotherapy, nanoparticles can be designed to subtly reprogram the tumor microenvironment so the immune system recognizes and clears the cancer. For chronic pain, the goal is slow, steady release of non-addictive therapeutics that allow patients to take a single dose weekly rather than multiple times a day. Recently, her group published work on nanoparticles to treat deep vein thrombosis, a dangerous condition in which blood clots form in the legs.

The fabrication process is just as critical as the applications. Pinkerton’s lab uses techniques such as flash nano precipitation—well-suited for hydrophobic small-molecule drugs—and an inhouse method she developed, sequential nano precipitation, which expands the range of drugs and particle sizes that can be manufactured. Both methods emphasize scalability. “One of the biggest challenges in nanomedicine is translation,” she says. “People design beautiful particles in the lab, but if you can’t manufacture them in quantity, they’ll never reach patients.”

Each nanoparticle is built with a core–shell structure: the therapeutic drug sits in the center, protected by an outer layer that influences where the particle travels in the body and how quickly the drug is released. By carefully tuning size, composition, and chemistry, Pinkerton’s team can control release rates, an essential factor for both safety and effectiveness.

Advances in AI are helping researchers mine decades of experimental data, identifying drug combinations and material properties that might otherwise be overlooked.

Her long-term vision is a kind of “plug-and-play” platform for drug delivery: a universal system adaptable across different diseases and drug types, from small molecules to biologics such as proteins and nucleic acids. “If you know the process and the platform, all you need to do is swap in the drug,” she says. “That lowers both the knowledge barrier and the cost, and accelerates translation into the clinic.”

Pinkerton is equally energized by the broader field’s rapid progress. Advances in AI are helping researchers mine decades of experimental data, identifying drug combinations and material properties that might otherwise be overlooked. At the same time, tools for studying how nanoparticles behave inside the body have grown far more sophisticated. “When I started, the assumption was simply that nanoparticles got into cells,” she says. “Now we can trace the exact mechanisms of uptake, trafficking, and tissue-level distribution. That deeper understanding opens up much more precise design.”

For Pinkerton, the collaborative environment at NYU is another essential ingredient. Drug delivery sits at the crossroads of materials science, biology, engineering, and medicine, and requires expertise across all those domains. “What’s wonderful here is that I can work directly with oncologists, clinicians, and biologists,” she says. “That kind of team science accelerates discovery.”

Nathalie Pinkerton

Nathalie Pinkerton