The Birds and the Bees

(Of Engineering)

How NYU Tandon is partnering with nature to develop new solutions to the challenges we face

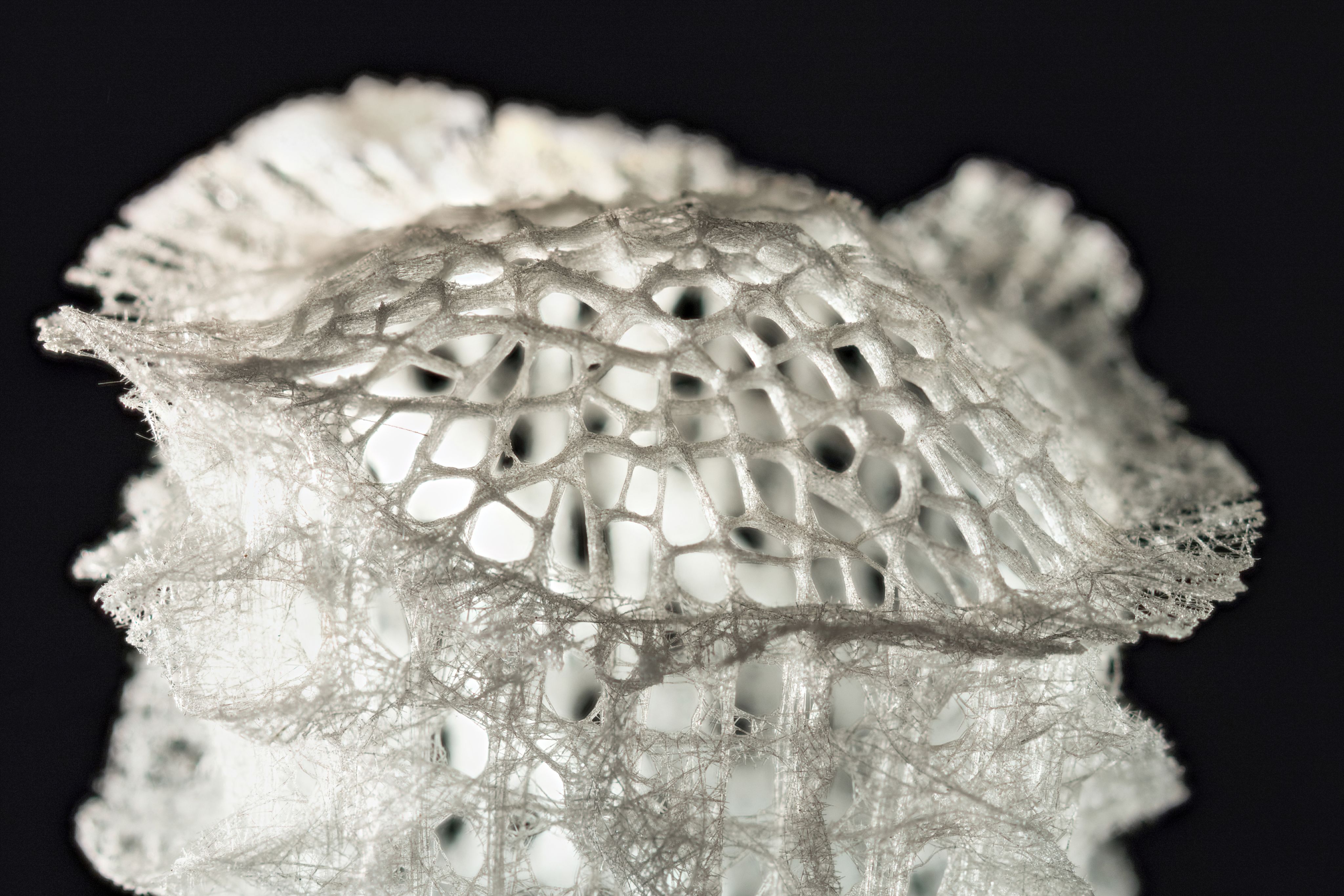

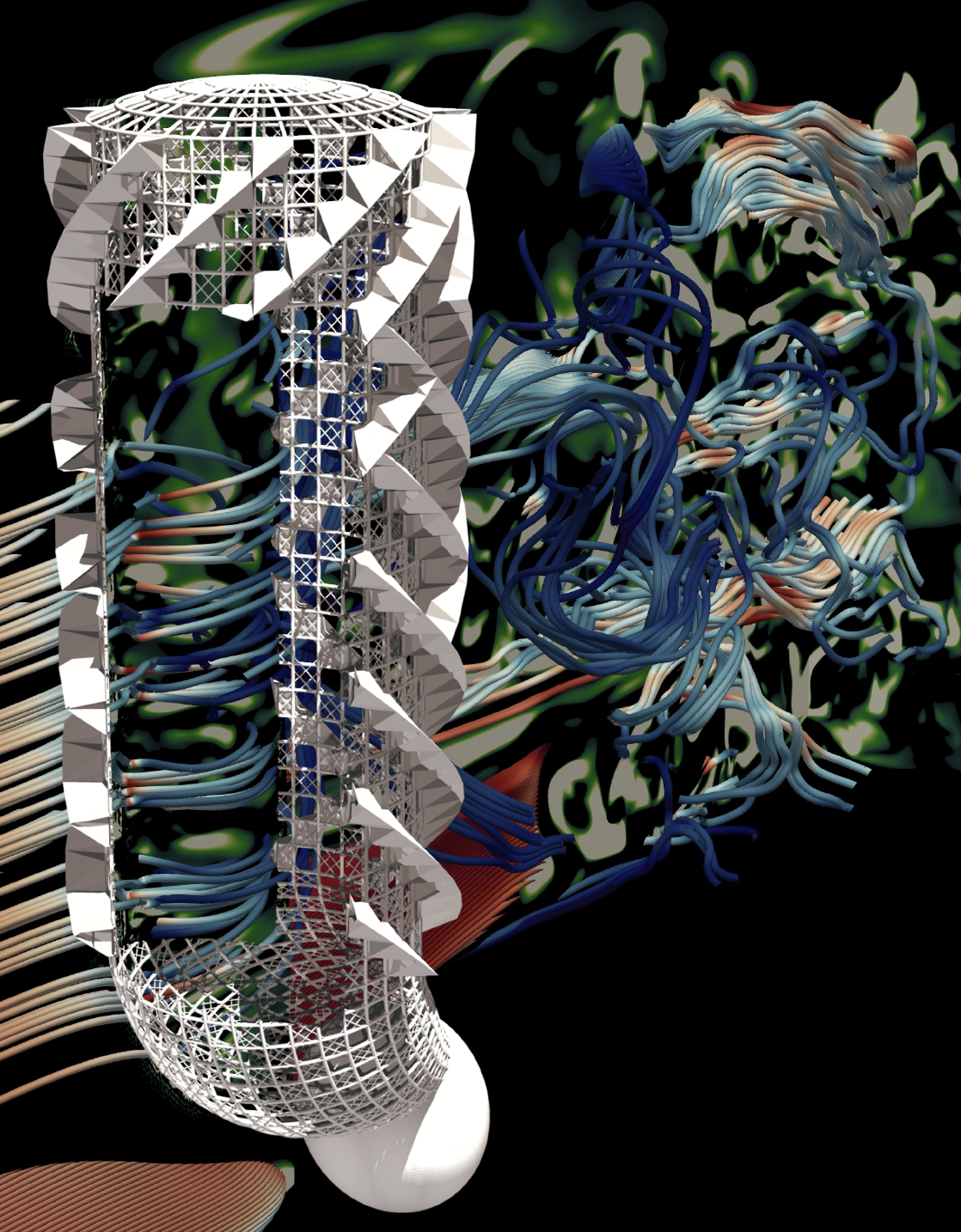

Hundreds of meters below the waves in total darkness, Venus’ flower baskets thrive anchored to the sea floor, withstanding powerful currents. Named for their intricate glass-like silica skeletons, these sponges feed by filtering bits of plankton and bacteria from relatively nutrient-poor ocean currents. Sometimes they’re found growing alone; other times clustered together like bouquets. For decades, their structural properties have mystified and fascinated engineers.

“These sponges are very special in the sense their skeleton is adapted to reduce the drag they experience, so they don’t break under the current in the deep ocean,” says Institute Professor Maurizio Porfiri, director of NYU Tandon’s Center for Urban Science + Progress focused on modeling complex systems.

Maurizio Porfiri

Maurizio Porfiri

Porfiri is the latest in a long line of scientists studying glass sponges. But he’s the first to simulate, using an Italian supercomputer, them in situ—modeling the flow of water through their bodies. His team’s models solved the mystery of sponge bouquets—they grow together because each individual sponge in a line benefits from a reduction in drag and easier feeding as some food passes through the sponge in front. The work led to a grant from the U.S. Navy to investigate whether glass sponge-inspired bulb structures attached to a ship’s hull could reduce weight and hydrodynamic drag to save fuel.

Besides porosity, glass sponges have another deep-sea superpower—helical ridges that divert water upward once it enters the body cavity, keeping nutrients inside the sponge longer. You can think of it, Porfiri says, like Leonardo da Vinci’s corkscrew helicopter. Watching the flow on his simulations, Porfiri’s mind raced with possible applications.

“Imagine a high-rise building that, rather than being a closed structure, will have an external shape that may look like the sponge with pores in certain places,” he says. The pores would reduce drag on the building, and a helical structure would redirect airflow upward past the building. “You can think of it sucking some air for the ventilation, and reducing the temperature at the street level.”

The glass sponge research was outside Porfiri’s wheelhouse—he recalls spending a long time asking biologists questions to “catch up.” But he loved it—curiosity drives all his research. “I like the idea of Leonardo da Vinci Renaissance science in which you’re not already specialized, you look at what you’re excited about, what you think has value,” says Porfiri. “I like to find analogies between fields, to see similarities and build bridges between areas.”

Many engineers look to biology for inspiration—to find designs evolution has already perfected and copy them. But Porfiri thinks it’s more complicated. “Evolution is not necessarily good, he says, “It’s very opaque.” If you copy an element of the natural world without understanding why it evolved the way it did. “You’re building a chip for an algorithm, but maybe the algorithm was meant for something else.” He sees his work as a two-way interaction between the animal kingdom and engineering—“scientifically principled biological inspiration.” And he’s not alone. Khalil Ramadi, a bioengineer at NYU Tandon and NYU Abu Dhabi, recently developed an ingestible pill inspired by the intricate, porous structures marine corals evolved to house microbial communities. Ramadi’s pill accurately samples the human microbiome in its path through the gut.

Porfiri’s colleagues at CUSP and across NYU Tandon are redefining what it means for engineers to learn from the natural world, from implications for urban design and improving cutting-edge technologies to new ways of sensing and perceiving the world around us.

Beehives as a barometer for urban health

During the record-breaking heat of the summer of 2010 in Brooklyn, a mystery captivated New York—beehives started producing red honey. Ultimately, the honey tested positive for Red No. 40, a food dye, and the culprit became clear—illegal dumping at a Red Hook maraschino cherry factory that turned out to be a front for a much more illegal marijuana grow operation.

Assistant Professor Elizabeth Hénaff’s reaction was different from that of most New Yorkers: “That seeded the idea that bees were collecting information about their environment beyond the pollen and sugar they collect,” she recalls. Hénaff, a microbiologist at TCS and CUSP, studies environmental microbiomes. Microorganisms are an “invisible but ubiquitous” part of city life, she says. They form a “layer” over the environment we see, sensing and interacting chemically with the world around us. Every element of the urban environment—from humans and dogs to trees and ponds—has its own microbial cloud, also called an aerobiome. By studying the urban microbiome and those clouds, scientists can extend their human senses to look at the city with “microbe eyes”—using bacteria and viruses as biological sensors.

Elizabeth Hénaff

Elizabeth Hénaff

Thanks to technological advancements, DNA sequencing is relatively cheap and easy for labs like Hénaff’s today. The trickier part of enlisting microbes as urban sensors turns out to be collecting microbe samples to analyze in the first place. Environmental microbiology labs historically outsourced that hard foot labor to students, such as the MetaSUB consortium that Henaff collaborated with while a postdoc at Weill Cornell Medicine which sent out students into the New York subway system with swabs.

“Then we landed on this idea that bees were kind of doing the same thing we were asking those hordes of undergrads to do, which is go out, interact with the environment and then come back to the same place,” she says.

Bees forage up to two miles from their home hive. As they fly across the city through microbial clouds, their sticky bodies pick up more than pollen—microbes, viruses, fungi and other tiny biological particles. When they enter their hives, they wipe their feet on the metaphorical doormat, shedding debris to keep their home clean. All Hénaff’s team had to do was collect that accumulated discarded material from the bottom of hives, rich in microbial biomass, extract DNA from it, sequence that DNA and analyze it to understand all the microbes New York bees interact with on a daily basis.

In hives, Hénaff found microbes related to plants, humans, aquatic environments—both things and places bees physically interacted with and microbial clouds they flew through. Her study compared hive-derived city microbiomes for New York with Venice and other cities—each had a unique signature, captured by bees. This work could eventually lead to microbial maps of cities.

Why does that matter? Research shows that an abundant and diverse environmental microbiome is important for human health—inhabitants of environments with low microbial diversity have higher rates of autoimmune conditions. An environment with ecological niches thoroughly occupied by commensal microbes is more resilient to pathogens than a sterile one. Microbial life predates multicellular life like us by billions of years—they oxygenated the atmosphere and engineered our planet’s surface. Designers of the built environment, Hénaff says, should consider how to foster microbially diverse environments in cities.

More recently, Hénaff has turned her microbe eyes to the Gowanus Canal, an EPA superfund site in Brooklyn, which for a century served as a de facto dumping ground for polluting industries like coal tar extraction. But in the toxic, black viscous sediment in the bottom of the canal, Hénaff discovered a rich, thriving microbial community—for each toxic compound present, a bacteria species with a genetically encoded metabolic pathway evolved to degrade it. This community of species has potential biotechnological applications—engineers could reverse-engineer those pathways and use the microbes in bioremediation efforts. But more interesting to Hénaff is the “poetic aspect”: the canal’s microbiome maintains a record of a century of human intervention in the environment. She compared the microbes present in the canal with New York’s records of contamination, and found “the microbe-kept record might be more accurate than the human-kept record.” Some microbes she found had bioremediation pathways for toxic compounds that EPA chemical analysis methods missed in the canal waters.

Hénaff is now working to develop microbe-based methods to test for environmental contamination. Traditional methods to search for organic compounds or heavy metals rely on expensive lab techniques like mass spectrometry or x-ray fluorescence. Detecting a particular DNA sequence that corresponds to a bacteria species that breaks down cadmium, for example, is cheaper and easier using the same common DNA sequencing technology that made widespread rapid PCR testing for Covid-19 possible.

Today, the city is dredging the Gowanus and capping its sediment with an impermeable layer to remediate the superfund site. That’s good for human health and reducing exposure, of course. But Hénaff thinks it’s also worth mourning the thriving microbial community caught in the crossfire—one that’s been valiantly degrading our waste for years. It’s at least worth keeping the microbes in mind.

“We think that we design cities for humans, but actually they’re occupied by a multitude of different species, and the design decisions we make for humans, like a pretty pond in Prospect Park or what kind of tree species we plant or what’s our trash management system, inadvertently impact all the other species that inhabit these environments,” she says. “So you can think of the city as a superorganism in a certain sense, mediated by all the microbial interactions between species.”

Lessons from birds and bones

As artificial intelligence technologies advance, computer scientists and engineers at Tandon are increasingly teaming up with biologists to help unlock the natural world’s mysteries. To help ecologists track migratory songbirds, Professor Juan Pablo Bello (CSE, ECE, CUSP) set out to build machine learning software that could identify birds by listening to the short calls they emit in flight. He didn’t expect lessons from those birds on how to better design AI systems. But that’s exactly what happened.

Juan Pablo Bello

Juan Pablo Bello

A major challenge in machine listening is training a system to recognize patterns independently of context—a system designed to detect human speech needs to be able to identify a person speaking if they’re in a quiet forest or a loud construction site. Computer scientists call that intentional blindness to context “invariance.” With Bello’s bird detection bioacoustics project, called BirdVox, much of the complex signal processing under the hood went toward automatically filtering background noise. But listening to birds taught Bello that fundamental goal might be misguided.

“With birds a very interesting phenomenon in cities is they modify their song as a function of the noise where they are,” says Bello. Some birds change their pitch enough to compete with the din of city noise that the system misidentified their calls based on frequency. The environmental noise is more than noise—it’s important context for understanding the range in variability within a species, he says. Filtering it out means losing key data.

Computer scientists “have a lot to learn about adaptability in biological systems,” says Bello. The BirdVox project highlights a need to “treat variation as a function of context,” in AI systems, which is not the norm now. “There is a relationship between context and content here, which in machine learning you try to ignore, right?” says Bello. “But in the real world, those relationships are actually important to understand what is going on.” Moving machine learning forward from classification and identification to true reasoning, the next paradigm shift, will mean rethinking assumptions about data and signals, he says.

While developing BirdVox, Bello also studied urban noise in New York City through a project called SONYC. The team’s sensors went up as pandemic lockdowns began and quickly detected a pattern many New Yorkers noticed—birds returning to spaces temporarily abandoned by cars and humans. From the birds, Bello learned another lesson for machine learning—the importance of cyclicity.

“You naturally think of cyclical behavior as hours in the day, and for birds that’s a lot less relevant than hours as a function of sunup,” says Bello. Since birds are most active at dawn, a machine listening system has to be on its game then more than other times of day when there are fewer simultaneous calls to differentiate. In the city studying urban noise, Bello noticed similar circadian rhythms in sound that varied by day of the week, month and season. Those rhythms made self-supervised learning possible—his team could tell the SONYC system that a synagogue call happens at a specific time every day, and the system could use that intrinsic element in the data to learn to identify the sound of synagogue calls. “That was an interesting thing grounded on what we observed with birds early on,” he says.

Bello isn’t the only computer scientist at Tandon learning from the natural world in efforts to help biologists with research. While he develops computer ears to supplement scientists’ hearing, Assistant Professor David Fouhey (ECE) is working in the more mainstream field of computer vision, supplementing their eyes. Computer vision has been around a long time—one of its earliest innovations was the facial recognition systems that made digital camera autofocus possible. Now, AI analysis of imagery enables everything from autonomous driving to 3D building models in Google Maps.

David Fouhey

David Fouhey

In 2019, Brian Weeks, an evolutionary ecologist at the University of Michigan, reached out to Fouhey. He had a problem—he wanted to study changes in bird skeletons over time using museum collections. He knew museums had centuries of specimens stored in little boxes—tons of data. But going through that data proved immensely challenging.

“You have this amazing commitment to collecting data, but the problem is you have to get someone who can reliably identify, say, swallow tibia out of a collection of bones,” says Fouhey, “You gotta find the bones, handle them really carefully and measure them with calipers, and so it takes a surprisingly long time.” And in terms of labor, it’s expensive.

As part of the project, Fouhey got a behind-the-scenes tour of the Natural History Museum in New York, a favorite childhood destination. In the back rooms, it’s “like in Indiana Jones,” he says—imagine warehouses full of crates and lockers of carefully collected samples. The problem seemed immense.

Together, the duo worked on a solution. Weeks built a contraption to photograph specimens from above using a digital camera, and Fouhey created a computer vision machine learning system that they trained to recognize specific bones and then measure their lengths at high accuracy, even when bones were mixed up on top of each other. They called the system “Skelevision.”

With about a month’s scanning effort , they’d measured 10,000 samples—an order of magnitude more than they could have with traditional methods. And the project paid off—the dataset Fouhey helped Weeks unlock confirmed that Allen’s Rule, which holds that animals in warmer climates have longer limbs, also applies to bird wings. Previously, biologists weren’t sure whether bird wings were exempt from the rule—their size determined only by the bird’s flight needs. It turns out wings, like other limbs, also dissipate heat.

Like Porfiri, Fouhey found himself well outside his comfort zone. “The big challenge is all of a sudden you’re doing stuff that you have no training in at all,” he says. He asked a lot of “stupid” questions, like “Why on earth are you so obsessed with the length of bird femurs?” But also, like Porfiri, he loved it. “What’s so fun is you chat with these scientists and they have all these interesting practices and they’re things you never knew about, like wait, that’s how this works?” He learned each museum keeps a drawer of beetles on hand to clean the flesh off bird bones, for example. Fouhey used to take birds for granted, but now he’s an avid birder on vacations, he says. And he’s worked on other projects for scientists, including computer vision approaches to solar physics data.

From the bird bones project, Fouhey also came away with lessons for the AI and machine learning field. Evolutionary biologists care about uncertainty quantification and high accuracy, even at the expense of leaving out some data, he says. AI developers are very excited if a system hits 80% accuracy—for a scientist, that’s unusable. AI researchers can also get carried away with complexity—this project taught him to slow down and find the simplest solution to the scientists’ problems.

AI for scientific research is “heating up” as a field, Fouhey says. Deep learning, the basis of computer vision, used to be a topic that would get your paper dismissed at conferences. But NYU has allowed its computer scientists to work on it for years, and now it’s paying off. Together with a passion for interdisciplinary work among faculty, that willingness to support work that will be impactful a decade down the line makes projects like his possible.

“You have to do your time and sit and get corrected on unitsat by plasma physicists and call up bird people and have them say, ‘No sorry, I’m off in the Upper Peninsula checking out nests.’ It takes a long time to build that. And NYU is the type of place where you can do that. And I think that’s exciting; it’s engineering work aiming to solve concrete problems and is focused on the future.”

From the bird bones project, Fouhey also came away with lessons for the AI and machine learning field. Evolutionary biologists care about uncertainty quantification and high accuracy, even at the expense of leaving out some data, he says. AI developers are very excited if a system hits 80% accuracy—for a scientist, that’s unusable. AI researchers can also get carried away with complexity—this project taught him to slow down and find the simplest solution to the scientists’ problems.

AI for scientific research is “heating up” as a field, Fouhey says. Deep learning, the basis of computer vision, used to be a topic that would get your paper dismissed at conferences. But NYU has allowed its computer scientists to work on it for years, and now it’s paying off. Together with a passion for interdisciplinary work among faculty, that willingness to support work that will be impactful a decade down the line makes projects like his possible.

“You have to do your time and sit and get corrected on unitsat by plasma physicists and call up bird people and have them say, ‘No sorry, I’m off in the Upper Peninsula checking out nests.’ It takes a long time to build that. And NYU is the type of place where you can do that. And I think that’s exciting; it’s engineering work aiming to solve concrete problems and is focused on the future.”