NYU Tandon Helps Digitize Decades of City Data

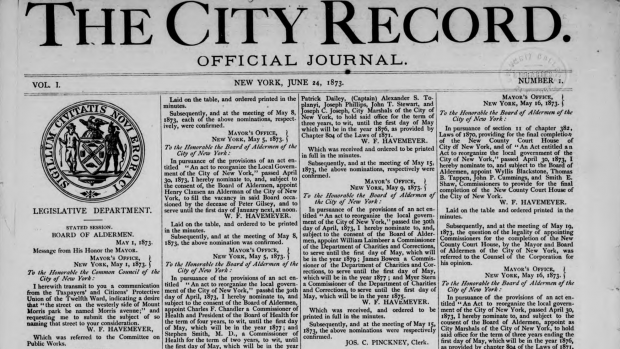

The first edition of The City Record, a daily paper launched in 1873. The archives are now searchable thanks to a grant NYU Tandon received from the National Endowment for the Humanities to digitize the publication.

Stand near the intersection of 10th Avenue and 70th Street in Manhattan today, and it might be hard to imagine the bustling intersection as being described as bucolic. Most city dwellers are now living on what was once farmland, however, and in 1875 that spot was home to several newly purchased cows whose owner had been granted the required permit.

That information comes courtesy of The City Record, a daily paper launched by urban reformers to promote government transparency after the Boss Tweed scandal and published every weekday, except for legal holidays, since June 24, 1873.

While it might seem daunting to search for specific information in the publication’s thousands of volumes (comprising more than a million pages), the prospect recently became magnitudes easier thanks in large part to the NYU Tandon School of Engineering.

In 2016 the School was awarded a highly competitive $260,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to digitize the publication, making it easy to search and freely available to the public. Now, visitors to the newly unveiled portal can enter keyword or date to discover rich troves of data on the city’s economy, real estate and infrastructure development, agency expenditures, crimes, and political scene.

Led by Jonathan Soffer, a professor of history and chair of Tandon’s Department of Technology, Culture & Society, the digitization project has thus far encompassed daily volumes from 1873 through 1947, and its second phase will cover 1948 through the beginning of the 21st century, when the paper began automatic digital publication.

Soffer — whose colleagues on the project include Luke DuBois and Dana Karwas of Tandon’s Integrated Digital Media program, as well as Columbia University urban economist Donald Davis — explains, “The digitization of The City Record will have an important impact on urban history and economics, and across the social science disciplines. No other city of New York’s size and importance provides a comparable historical database.”

Soffer credits the New York Public Library and NYC Department of Records for their support of the project, and he hopes to one day geo-tag the data, so that users can simply click on a map to find relevant information.

Although it provides an obvious bonanza for amateur historians and trivia lovers, the portal is geared towards aiding serious scholars and social scientists. By way of example, Soffer cites the published lists of New York City residents who have died intestate; when cross-referenced with immigration records, a fascinating portrait emerges of which groups thrived after settling in New York City and which did not.

Whether scholarly or merely curious, all researchers will now have easy access to an abundance of data, including City Council meeting minutes; weekly reports on mortality and health; the disposition of lawsuits against the city; countless documents that touch upon the fabric of everyday life in New York City, such as the very first traffic code for automobiles in 1901; citizen complaints; employment records; and lists of unclaimed property left by prisoners, to name just a small sample.

Interested in how much the volunteer fire department in the borough of Richmond — now known as Staten Island — spent on pieces of apparatus in 1905? The answer is $68. Who were the police seeking in September of 1877? In one case, they were on the lookout for the owner of a lost bay mare standing slightly more than 16 hands high, with a white star on its forehead.

That information and much, much more is now only a few clicks away.