Sensors and the city

NYU Tandon faculty use the devices to tackle tough problems plaguing New York and other cities

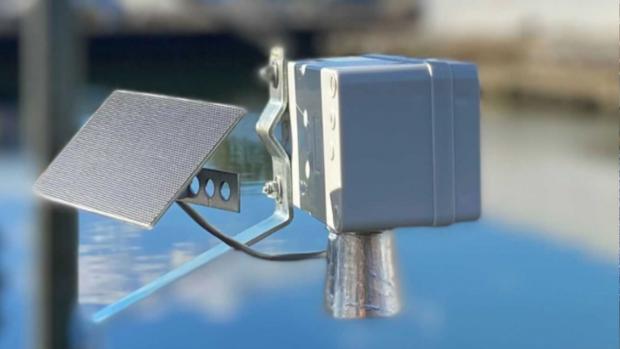

A flood sensor used in FloodNet, a project that captures data on urban flooding

On October 22, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers hosted a webinar, “How Sensors are Making Better Urban Environments, featuring two experts: Center for Urban Science and Progress (CUSP) Research Assistant Professor Charlie Mydlarz, who also works with the Music and Audio Research Laboratory at NYU Steinhardt, and Tandon Assistant Professor of Civil and Urban Engineering Andrea Silverman, who is affiliated with CUSP, C2SMART, and the NYU College of Global Public Health.

During the event, which drew some 400 viewers, Mydlarz discussed Sounds Of New York City (SONYC), an initiative aimed at mitigating one of the most common civic complaints in New York: excessive noise. SONYC researchers, including CUSP director Juan Pablo Bello and co-PIs Claudio Silva, R. Luke DuBois, and Oded Nov, have deployed more than 75 sensors over the last five years, collaborating with seven city agencies and three Business Improvement Districts to gather 200 million audio recordings and 75 billion rows of decibel data in order to better understand noise levels in outdoor environments and deep learning based algorithms to identify the sources of sound contributing to these environments.

Among the important points Mydlarz made:

- Projects like SONYC owe their success to major advances in sensor and edge-computing technology made over the last decade; the emergence of the maker movement and citizen science; and increased cooperation from municipal officials.

- Researchers can’t simply rely on noise complaint calls, because they are reactive (meaning they might be made well after the noise has abated) and the data that results contains inherent bias. (Consider, for example, that a preponderance of complaints from residents of the Upper East Side might not mean it’s the noisiest area of the city but that people who live there are more adept at navigating the city’s 311 reporting system.)

- While recording audio understandably brings up issues of privacy, SONYC researchers are careful to collect only randomly spaced, short, encrypted snippets of sound; sounds confirmed as speech are not intelligible to external consultants; and edge audio processing means there is no need for transmission, eliminating many concerns

- Proof of the project’s effectiveness can be found in the passage of the Resilient Red Hook Community Resolution, which emerged after a sensor deployed on Brooklyn’s Van Brunt Street revealed excessive amounts of noise from trucks

- The SONYC team, working closely with the Department of Environmental Protection, is currently distributing sleekly designed, exterior window mounted sensors to individual home-owners or renters who have made noise complaints, in an effort to facilitate data-driven enforcement of noise regulations.

Silverman then explained FloodNet, a C2SMART-funded project that had its genesis when she and a few colleagues, including Mydlarz, Elizabeth Henaff and Tega Brain of Tandon’s Department of Technology, Culture, and Society, began thinking of ways to monitor the contaminants in urban floodwaters and realized there were few good sources of data on the frequency, extent, and depth of floods that had occurred, particularly in the case of “hyperlocal” incidents in which only certain neighborhoods or even blocks were affected.

FloodNet, a collaboration with the City University of New York and NYC agencies, is aimed at obtaining real-time data as floods occur, and the team has installed sensors throughout the city, particularly in areas prone to pluvial flooding from heavy rains and coastal areas at the mercy of storm surges or high tides. Their work, the researchers hope, will improve resiliency and transportation planning by city agencies, allow for more localized activation of emergency response centers, inform day-to-day decision-making; and encourage activism in the communities hardest hit.

Silverman pointed out:

- Urban flooding is a serious issue that can cause infrastructure damage, mobility problems, and severe threats to public safety

- The sensors are low-cost, robust, and independent of power and internet connection, which allows flexibility in deployment

- Flood depth data is collected every minute, allowing measurement of flood profiles in real-time

- Data were collected from sensors in Gowanus and Hamilton Beach during extreme storms Ida and Henri, and illustrated the severity of flooding caused by extreme precipitation

- In the future, the FloodNet team plans to deploy more than 200 additional sensors, continue to develop new hardware and software and strengthen the project dashboard; improve data analysis to extrapolate flood depth to horizontal extent; and increase community engagement