A Champion for Innovation

Meet Tandon’s Vice Dean for Research, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Kurt Becker

Throughout its history, Poly faculty, students, and alumni have been prolific inventors and innovators. More often than not, these efforts were the result of individual creativity, drive, and persistence, sometimes combined with serendipity. There was no institutional culture or support of what we now refer to as academic entrepreneurship. This began to change in 2005 when Jerry Hultin, then the dean of the Wesley J. Howe School of Technology Management at Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, NJ crossed two rivers to assume the presidency of Poly. Within a year, he recruited his former Stevens colleague Erich Kunhardt (who happened to be a Poly and NYU alumnus) as his provost.

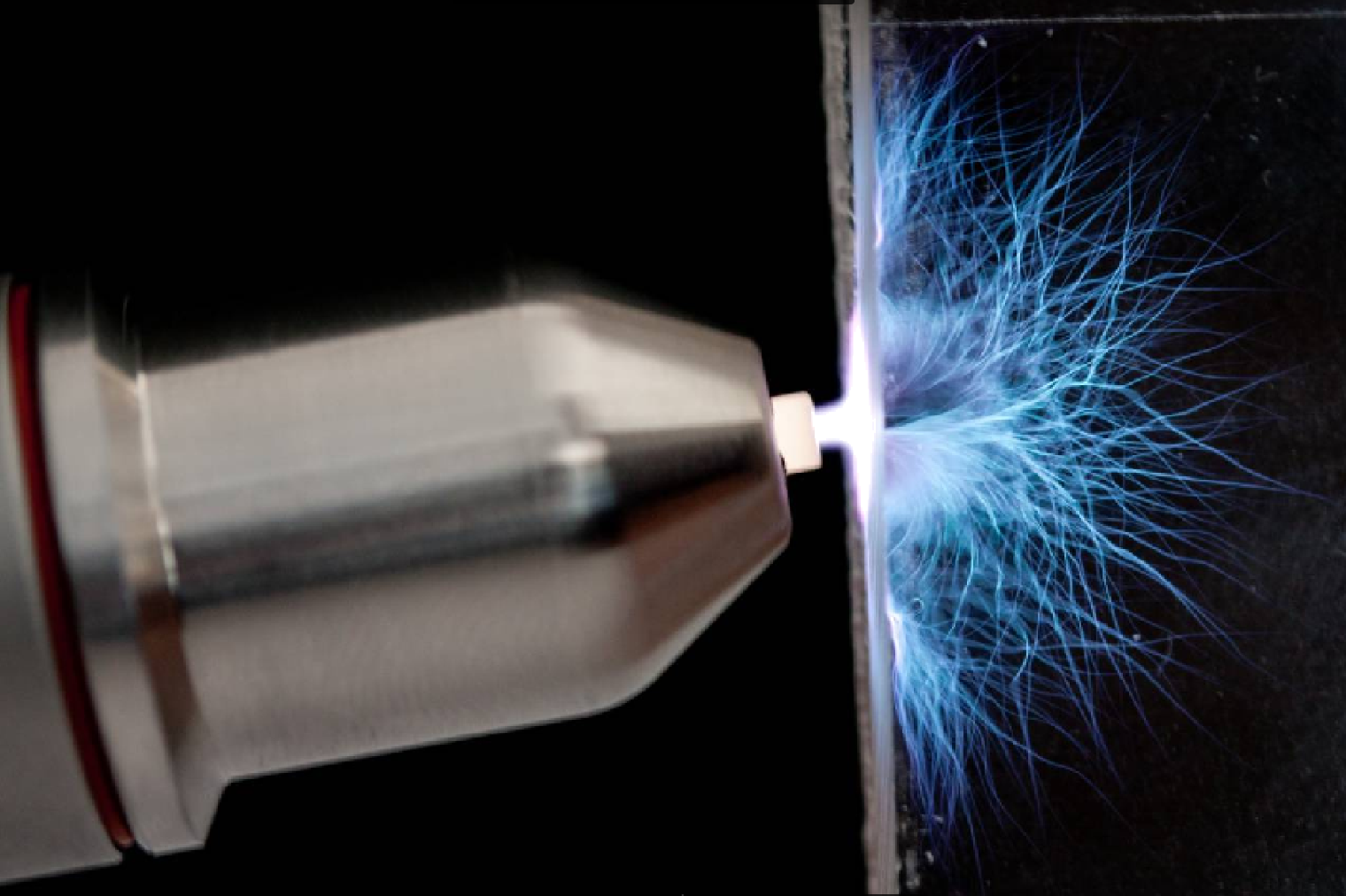

Argon plasma jet penetrating a narrow slit to treat

the inner surface of an object

Kunhardt had worked closely at Stevens with Kurt Becker, who headed the institute’s Department of Physics and Engineering Physics and also served as the associate director of its Center for Environmental Systems. They had conducted pioneering research into the stabilization and maintenance of atmospheric-pressure cold plasmas and patented their findings. These patents paved the way for the development of technologies that led to new, more effective methods of sterilizing medical instruments, killing bacteria, performing environmental remediation, and other applications. Becker and Kunhardt commercialized this new technology through two start-ups, one of which was later acquired by the medical device and equipment manufacturer Stryker Corporation.

Wanting to encourage Poly’s faculty members to commercialize their research in that same way and creating a supportive institutional environment to do so, Kunhardt, in 2007, brought Becker to Poly as associate provost for research and technology initiatives.

In the Beginning

While a first start-up incubator was established in the basement of Rogers Hall, it was, as Becker explains, “a great idea just a few years too early.” New York City was not yet the entrepreneur-friendly city it was soon to become, and given that there was little faculty buy-in and no alignment between entrepreneurship and the school’s academic mission, the incubator was not a big success.

Not long after Becker’s arrival, however, New York underwent a transition: in the wake of the financial crisis that upended the city’s economy, government officials realized the need to diversify the economic basis of the city by encouraging entrepreneurial activities, a start-up culture, and incubators. The city’s Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC) joined forces with the school to launch the Varick Street Incubator — one of the first such facility supported by the city. That same year, the school opened the Accelerator for a Clean and Renewable Economy (ACRE), thanks to an initial $1.5 million grant from the New York State Energy and Research Development Authority (NYSERDA).

The Start of Something Big

Today, Becker oversees the large network of programs that ultimately grew from those initial efforts. In 2011 another incubator was launched in the DUMBO section of Brooklyn, and by the end of 2013 the total economic impact of the Poly incubators was measured at more than $350 million thanks to the number of jobs created, capital raised, and tax revenue generated.

Becker explains that the term incubator is no longer accurate. “While we used to focus on early-stage companies, we’ve pivoted to supporting those at the seed stage with a minimum viable product (MVP),” he says. “They can remain tenants for up to two years, until they receive their Series A round of financing. It’s more accurate to say that the incubators have morphed into technology acceleration and commercialization hubs.”

— Kurt Becker

Tandon now calls the former incubators Future Labs: its Data Future Lab houses companies working in the realm of data-driven and data-intensive technologies such as machine learning, artificial intelligence, blockchain, and others, while the Digital Future Lab is home to several hardware and digital media firms and attracts start-ups in virtual reality and augmented reality. The Urban Future Lab (UFL) functions as a hub for smart cities, smart grid and clean energy technologies; ACRE is now located there, as is PowerBridgeNY, a cleantech proof-of-concept center, and Clean Start, a cleantech workforce training program. Tandon also recently added a Future Lab aimed at military veteran-owned businesses.

“The Future Labs are much more than co-working spaces,” Becker says. “All the companies that are accepted get the benefit of expert business and support services, introductions to angel investors and venture funding, faculty expertise, and student talent.” About a third of the companies in the Future Labs are NYU-affiliated in some way.

The Academic Piece of the Puzzle

Ever since Becker, who is also a professor of both applied physics and mechanical and aerospace engineering, came to Brooklyn, one of his responsibilities has been to help imbue the school’s academic offerings with entrepreneurial spirit.

From the minute freshmen set foot on the MetroTech Plaza, they are introduced to the idea of innovation and entrepreneurship through the required first-year Innovation and Technology Forum, they have access to the MakerSpace, and can compete in InnoVention, a student ideation-to-prototype competition as well as many other competitions across NYU such as Stern’s $300K Entrepreneurs Challenge. “We don’t exist in a vacuum,” he asserts. “We’re very lucky to be part of NYU’s entrepreneurial ecosystem, which includes the Leslie eLab, the Entrepreneurial Institute, the Stern W.R. Berkley Innovation Lab, and more.”

Faculty members are often more hesitant to take their science and engineering breakthroughs into the entrepreneurial world than their Ph.D. students and Postdocs. In an effort to help explore the full commercial potential of academic inventions, he helped ensure NYU’s entry into the consortium that comprises the National Science Foundation’s New York City Regional Innovation Node (NYCRIN), which also includes CUNY and Columbia. Part of the NSF’s groundbreaking Innovation Corps (I-Corps) program, the node aims to team academic researchers, Ph.D. students, and Postdocs with experienced entrepreneurs to accelerate the commercialization of their inventions. (The school also recently became an I-Corp Site, and that smaller entity’s focus will be on encouraging entrepreneurship among women and other underrepresented groups.)

The National Academy of Inventors

Becker with his 2017 City & State Sustainability & Environmental Impact Award

Becker is also largely responsible for the fact that NYU became first a charter member and subsequently a sustaining member of the National Academy of Inventors, which was established in 2010 to recognize academic inventors, enhance the visibility of academic entrepreneurship and innovation, encourage the disclosure of intellectual property, and translate the inventions of its members into new products and processes that benefit society. In 2013 he was elected as a fellow of the organization, in honor of his patents on the stabilization of atmospheric-pressure plasmas and their practical applications. He was named to the organization’s board of directors in mid-2016. Those prestigious posts are not his only laurels, however. Becker — who has authored almost 250 articles in refereed journals and books and more than 500 conference contributions and abstracts — was elected to fellowship in the American Physical Society in 1992 and has been the recipient of a 2001 Thomas Alva Edison Patent Award, the 2010 SASP Erwin Schrödinger Medal, and a 2017 City & State Sustainability & Environmental Impact Award, among other recognitions.

Outsiders may well wonder why a university is so immersed in the world of business and entrepreneurship, and Becker, a native of Zweibrücken, Germany, has a ready answer. “It’s part of our mission to find practical, real-world applications for our research,” he says. “We’re creating technology here that has the potential to solve some of the world’s most pressing problems.”