Adeen Flinker received a BA in Computer Science from Technion, Israel Institute of Technology, a PhD in Neuroscience from the University of California at Berkeley and he completed his post-doctoral research at New York University. He joined the New York University School of Medicine as an Assistant Professor of Neurology in 2017. He has appointments with the NYU Neuroscience Institute, NYU Biomedical Engineering and NYU Cognition and Perception.

The lab's research focuses on the electrophysiology of speech perception and production. He leverages behavioral, non-invasive and invasive electrophysiology in humans to tackle basic questions in the perception and production of speech and language. While most human research methodologies are limited to non-invasive techniques such as EEG (Electroencephalography) and fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) the Flinker lab focuses on collaborative research with rare neurosurgical patients undergoing treatment for refractory epilepsy. These patients are implanted with intracranial electrode grids placed directly on the surface of the brain for a one-week period in order to monitor and localize epileptogenic activity. While the electrode placement is driven solely by clinical necessity, during lulls in clinical care there is a unique opportunity to conduct cognitive tasks with patients in the hospital while Electrocorticographic (ECoG) signals are being collected directly from cortex. These neural signals provide an aggregate measure of neural excitability with combined temporal and spatial resolution. The focus of the research in the lab is to employ various experimental, machine learning and signal processing approaches to elucidate speech networks based on neural signals recorded directly from human cortex. Our goal is to further our understanding of how the human cortex supports speech perception and production while providing better tools for clinicians to map function prior to surgery.

Research News

Syntax on the brain: Researchers map how we build sentences, word by word

In a recent study published in Nature Communications Psychology, researchers from NYU led by Associate Professor of Biomedical Engineering at NYU Tandon and Neurology at NYU Grossman School of Medicine Adeen Flinker and Postdoctoral Researcher Adam Morgan used high-resolution electrocorticography (ECoG) to investigate how the human brain assembles sentences from individual words. While much of our understanding of language production has been built on single-word tasks such as picture naming, this new study directly tests whether those insights extend to the far more complex act of producing full sentences.

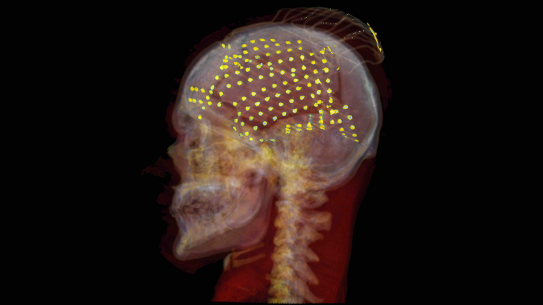

Ten neurosurgical patients undergoing epilepsy treatment participated in a set of speech tasks that included naming isolated words and describing cartoon scenes using full sentences. By applying machine learning to ECoG data — recorded directly from electrodes on the brain’s surface — the researchers first identified the unique pattern of brain activity for each of six words when they were said in isolation. They then tracked these patterns over time while patients used the same set of words in sentences.

The findings show that while cortical patterns encoding individual words remain stable across different tasks, the way the brain sequences and manages those words changes depending on the sentence structure. In sensorimotor regions, activity closely followed the spoken order of words. But in prefrontal regions, particularly the inferior and middle frontal gyri, words were encoded in a completely different way. These regions encoded not just what words patients were planning to say, but also what syntactic role it played — subject or object — and how that role fit into the grammatical structure of the sentence.

The researchers furthermore discovered that the prefrontal cortex sustains words throughout the entire duration of passive sentences like “Frankenstein was hit by Dracula.” In these more complex types of sentences, both nouns remained active in the prefrontal cortex throughout the sentence, even as the other one was being said. This sustained, parallel encoding suggests that constructing syntactically non-canonical sentences requires the brain to hold and manipulate more information over time, possibly recruiting additional working memory resources.

Interestingly, this dynamic aligns with a longstanding observation in linguistics: most of the world’s languages favor placing subjects before objects. The researchers propose that this could be due, in part, to neural efficiency. Processing less common structures like passives appears to demand more cognitive effort, which over evolutionary time could influence language patterns.

Ultimately, this work offers a detailed glimpse into the cortical choreography of sentence production and challenges some of the long-standing assumptions about how speech unfolds in the brain. Rather than a simple linear process, it appears that speaking involves a flexible interplay between stable word representations and syntactically driven dynamics, shaped by the demands of grammatical structure.

Alongside Flinker and Morgan, Orrin Devinsky, Werner K. Doyle, Patricia Dugan, and Daniel Friedman of NYU Langone contributed to this research. It was supported by multiple grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Morgan, A.M., Devinsky, O., Doyle, W.K. et al. Decoding words during sentence production with ECoG reveals syntactic role encoding and structure-dependent temporal dynamics. Commun Psychol 3, 87 (2025).

Mapping a new brain network for naming

How are we able to recall a word we want to say? This basic ability, called word retrieval, is often compromised in patients with brain damage. Interestingly, many patients who can name words they see, like identifying a pet in the room as a “cat”, struggle with retrieving words in everyday discourse.

Scientists have long sought to understand how the brain retrieves words during speech. A new study by researchers at New York University sheds light on this mystery, revealing a left-lateralized network in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex that plays a crucial role in naming. The findings, published in Cell Reports, provide new insights into the neural architecture of language, offering potential applications for both neuroscience and clinical interventions.

Mapping the Brain’s Naming Network

Word retrieval is a fundamental aspect of human communication, allowing us to link concepts to language. Despite decades of research, the exact neural dynamics underlying this process — particularly in natural auditory contexts — remain poorly understood.

NYU researchers — led by Biomedical Engineering Graduate Student Leyao Yu and Associate Professor of Biomedical Engineering at NYU Tandon and Neurology at NYU Grossman School of Medicine Adeen Flinker — recorded electrocorticographic (ECoG) data from 48 neurosurgical patients to examine the spatial and temporal organization of language processing in the brain. By using unsupervised clustering techniques, the researchers identified two distinct but overlapping networks responsible for word retrieval. The first, a semantic processing network, was located in the middle and inferior frontal gyri. This network was engaged in integrating meaning and was sensitive to how surprising a word was within a given sentence. The second, an articulatory planning network, was situated in the inferior frontal and precentral gyri, which played a crucial role in speech production, regardless of whether words were presented visually or auditorily.

Auditory Naming and the Prefrontal Cortex

The study builds upon decades of work in language neuroscience. Previous research suggested that different regions of the brain were responsible for retrieving words depending on whether they were seen or heard. However, earlier studies relied on methods with limited temporal resolution, leaving many unanswered questions about how these networks interact in real time.

By leveraging the high spatial and temporal resolution of ECoG, the researchers uncovered a striking ventral-dorsal gradient in the prefrontal cortex. They found that while articulatory planning was localized ventrally, semantic processing was uniquely represented in a dorsal region of the inferior frontal gyrus and middle frontal gyrus — a previously underappreciated hub for language processing.

"These findings suggest that a missing piece in our understanding of language processing lies in this dorsal prefrontal region," explains lead author Leyao Yu. "Our study provides the first direct evidence that this area is involved in mapping sounds to meaning in an auditory context."

Implications for Neuroscience and Medicine

The study has far-reaching implications, not only for theoretical neuroscience but also for clinical applications. Language deficits, such as anomia — the inability to retrieve words — are common in stroke, brain injury, and neurodegenerative disorders. Understanding the precise neural networks involved in word retrieval could lead to better diagnostics and targeted rehabilitation therapies for patients suffering from these conditions.

Additionally, the study provides a roadmap for future research in brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and neuroprosthetics. By decoding the neural signals associated with naming, scientists could potentially develop assistive devices for individuals with speech impairments, allowing them to communicate more effectively through direct brain-computer communication.

For now, one thing is clear: our ability to name the world around us is not just a simple act of recall, but the result of a sophisticated and finely tuned neural system — one that is now being revealed in greater detail than ever before.

Yu, L., Dugan, P., Doyle, W., Devinsky, O., Friedman, D., & Flinker, A. (2025). A left-lateralized dorsolateral prefrontal network for naming. Cell Reports, 44(5), 115677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2025.115677