A Truly Private Life

Bruce Schneier is a self-proclaimed short-term pessimist and long-term optimist. He suspects that in future generations—similar to how we now judge the actions of the early industrialists of the early 1900s and their apparent lack of environmental concerns—we will look back onto the early information age and judge it just as harshly.

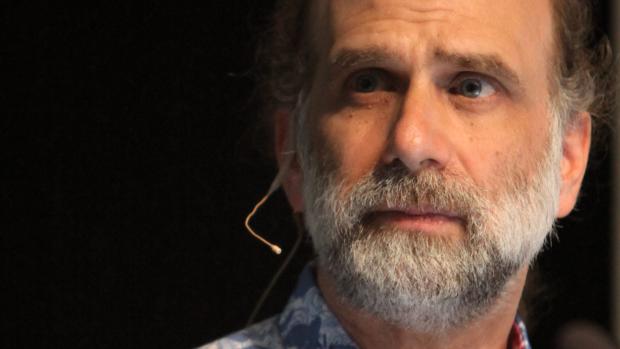

Schneier, a renowned security technologist and author of Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battles to Collect Your Data and Control Your World (along with twelve other books on digital security and privacy), visited the School of Engineering to discuss his latest book and the security—or lack thereof—of our digital information and what steps should be taken to curb this constant breach of privacy.

The first thing that was explained by Schneier was how data is, in effect, a byproduct of the information put into a computer, smart phone, or tablet. SMS messages and emails create automatic archives of our records. “It’s easier to save everything than to figure out what to save,” noted Schneier.

While in the past, humanity generally saved things for posterity or to keep a record of something, such as a contract, we now lean toward saving things in order to make decisions to act in the future. This is what Schneier calls “ubiquitous surveillance.” “Instead of ‘follow that car,’ it’s ‘follow every car.’ Follow that car last month, last year. Follow it back in time.”

This switch in thinking—and what ultimately lead to governmental surveillance practices—is partially because of the events of 9/11. The NSA, previously focused primarily on international espionage, was given an impossible mission: “never again.” Given the task of preventing something from happening naturally leads to the goal of learning everything that happens. Data that’s collected through cell phones and computers, originally taken to personalize advertising, was utilized by governments and allows them to achieve a startling level of surveillance. Schneier noted this as such: “We don’t tell the government when we make a new friend, but we let Facebook know. We don’t give the government every bit of correspondence, but we put everything on Google.”

The current move to cloud computing, instead of leaving our precious data on physical hard drives close to us, also follows this trend. Historically, humanity tended to keep important documents close—the exact opposite of what cloud computing achieves. In a similar vein, software in tablets and smart phones has tighter reign over what apps the consumer may run and more concessions are being given to the makers to retain information. Our data, ultimately, is not under our control. When this data is stolen in huge data breaches, it is even less so.

With all of these scenarios in mind, Schneier highlighted what would alleviate further impingement on civilian data: prioritizing security over surveillance, true transparency within the government and its programs, oversight and accountability for extreme failure within the system, designing for resilient systems, writing more comprehensive data protection laws, and creating answers with the expectation that the technology will be used worldwide. Schneier elaborated the last point by mentioning that, “if you create a system that allows everyone to easily collect information, governments as well as criminals, you need to keep this in mind; one world, one network.”

Schneier also voiced hope that the American public is truly beginning to understand the seriousness of the issue, citing that 700 million Americans changed their online habits and attitudes because of the revelations leaked by Edward Snowden. “Like a lot of social changes, I suspect this will go from impossible to inevitable in a short amount of time.”