The Remarkable Reisers: the inspiring life and work of an NYU-Poly professor

|

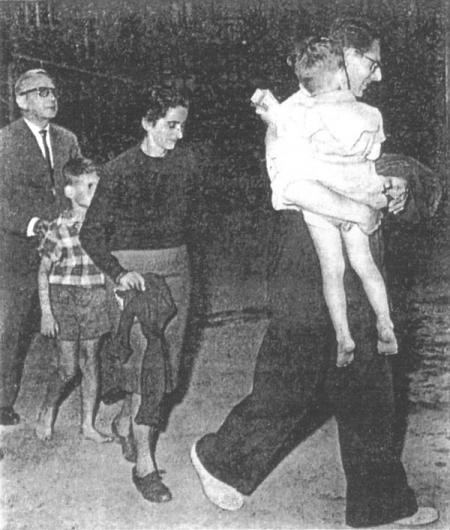

| A front-page picture from a major Danish newspaper shows the Reiser family arriving safely at the dock — free at last. |

This article previously appeared in Professor Mark Green’s blog “Science from Away.” If you have blog posts, or story suggestions for NYU-Poly News consideration, send them to the editor.

Imagine secret police, working in pairs as they often do, telling you to spy and report on a “suspicious” neighbor. Imagine their threats should you fail to comply: your views would be labeled antigovernment and therefore you could not be proper socialist parents and your two children could be torn away from you. Imagine you’ve heard of parents being sent to labor camps and mines, their children left orphaned. In such conditions you might well take these threats seriously.

In the 1950s, Polytechnic Institute of NYU professor Arnost Reiser and his wife Ruth had already lived long under the suspicions of oppressive Czechoslovak authority. Although not a victim of the several purges in the early 1950s, professor Reiser was known to associate with many people who had been purged. Moreover, although given the opportunity, he had never joined the “Party.” Thus, the Reisers were suspected of harboring dangerous views. The secret police may even have imagined that Arnost and Ruth escaped the gas chambers in Auschwitz — where they met during World War II — because the Nazi’s looked favorably on their purported anticommunist views. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth.

Arnost and Ruth decided that they had to escape but they were under suspicion. Remarkably, in the face of this suspicion by the authorities — likely aided by the incompetence of the Soviet enforced regime in Czechoslovakia — Arnost and Ruth passed through a sieve of safeguards. This multiple filtering process, led by “authentic” communist authorities, neighborhood groups and police, was designed to ensnare families like the Reisers. Fortunately, they quietly secured papers that allowed them a vacation trip out of the country. The first phase of their escape plan was in place.

Aboard the East German vacation ship Seebad Albeck, as it stood off the Danish coast, Arnost gave the sign and watched as Ruth and his son Jan leapt into the frigid waters of the North Sea. A crewmember shouted, “Ja was ist den de los,” and grabbed Arnost’s jacket. Twisting away, Arnost held his infant son Paul close and jumped from the ship. The shock of the jump and freezing water woke Paul, whose shriek startled the ship’s passengers into silence. Seeing Ruth and Jan ahead of him, approaching the dock at Gedser in Denmark, he began swimming, with baby Paul in his arms. If they could make it these last hundred meters, they would finally escape their oppressive past and begin life anew as refugees in a neutral nation. The East German guards were hesitant to fire their weapons: perhaps from humanity, perhaps because the ship was in Danish waters and being watched by Danes, who saw the scene unfold from the nearby dock. For whatever reason, no shots were fired, and the Reiser family arrived safely at the dock — free at last.

Shining light on the beautiful chemistry of microlithography

Arnost Reiser had been professor of physical chemistry at the Technical University in Prague and was known by certain influential scientists in England. Using these connections, the family was able to emigrate from Denmark to England, eventually becoming English citizens. Shortly after arriving in England in 1960, Dr. Reiser went to work at the Eastman Kodak Company on imaging technology. He remained there for many years, eventually ascending, upon the strength of his many accomplishments, to a position of scientific prominence at the company.

On retiring from Kodak, nearly 25 years ago, Arnost accepted an offer to move to the United States and organize an institute at Polytechnic for the exploration of the chemistry responsible for microlithography. Lithography is a rather important technology. Google the word and you will come up with over two and one half million hits. Visit Wikipedia and you will discover that this basic printing technology in microscopic form, microlithography, is responsible for the manufacture of the chips in our computers — important stuff.

|  |

| Arnost and Ruth Reiser on their wedding day | Dr. Arnost Reiser in his office in Rogers Hall |

The original chemical process that has evolved to produce computer chips started in the 1950s at a chemical company in Wiesbaden, Germany with an accidental observation of what happened to a chemical mixture upon exposure to sunlight. The areas on a specially made film could, when exposed to the light, be dissolved away (become soluble) from the rest of the film, which would not be affected. Therefore, by controlling the exposed parts of the film an image could be formed. This is just as in photography, where an image is formed by exposing silver salts to light. The silver salts are changed while the rest of the film is left unaffected. But this new process allowed imaging technologies not possible with photography.

For forty years, until professor Reiser’s investigations, the light in this new process was thought to cause a chemical reaction that released an acid substance, which was thought to be responsible for making soluble the light-exposed film. Gradually, it was discovered that controlling, with great precision, where the light shone on the film allowed for the formation of microscopic lines on a chip. These lines are responsible for directing the flow of electrons that control a computer.

Reiser’s investigations revealed that the long held belief of light’s role in the process could not be correct. Instead he realized that the area exposed to the light underwent a chemical reaction that gave off a great deal of heat, and it was the heat that caused the film to become soluble. He showed that the reason behind the solubility was that the heat disrupted a kind of chemical interaction. In fact, the interaction, hydrogen bonding, is one of the most important in the molecules that are responsible for life. But here they are encountered in a system that has nothing to do with biology. How beautiful.

Professor Reiser published his results, demonstrating that film production could be made simpler by allowing light to bring in the necessary heat directly by using infra-red lasers. Large corporations — Kodak-Polychrome, Agfa, Fuji and Mitsubishi — immediately jumped on the discovery. This new method of lithography has now grown into a multibillion-dollar industry. Meanwhile, its mild-mannered progenitor sits quietly in his office, deep in thought amidst his collection of books continuing to contribute new insights into the microlithographic process.

Not far from ninety years old, professor Arnost Reiser has endured such tragedy as most of us can only imagine. He has shown the courage and bravery we strive for on our best days. He has dreamed wonders that power the world around us. And he still feels fortunate to return home to Ruth’s dinners each night. Quiet heroes like the Reisers don’t clamor for attention or seek the spotlight. But we at NYU-Poly can feel proud knowing that Professor Reiser is one of us.