Professor Brain Discusses Machine Learning and Bias: The Story of the Enron Email Archive

NYU Tandon industry assistant professor Tega Brain of the Department of Technology, Culture and Society (TCS) co-hosted an event at the New Museum in response to her project, The Good Life — a collaborative venture with artist Sam Lavigne that is currently in an online exhibition at the New Museum. The work centers on the Enron Email Corpus and explores machine learning, bias in datasets, and email. In a panel moderated by Kate Crawford, NYU Tandon TCS distinguished research professor and co-founder of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) Now Institute, artists and computer scientists discussed the role that the Enron Corpus has played training natural language systems.

Kate Crawford (center) leads a panel of artists and researchers, including Brain, who discussed dataset bias and the Enron email archive's lasting impact.

The Enron Corpus is an archive of over 500,000 emails exchanged between Enron executives and was made public by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission during their investigation into Enron after its corporate corruption scandal and bankruptcy in the early 2000s. It is one of the most well-known and uniquely public email datasets, and with content that encompasses corporate intrigue and personal affairs, the archive has widespread use in artificial intelligence and natural language processing systems. “The archive has been an invaluable resource for computer scientists, who used it to train spam filters and other early machine learning systems, and apparently the first version of Apple’s Siri,” Brain said.

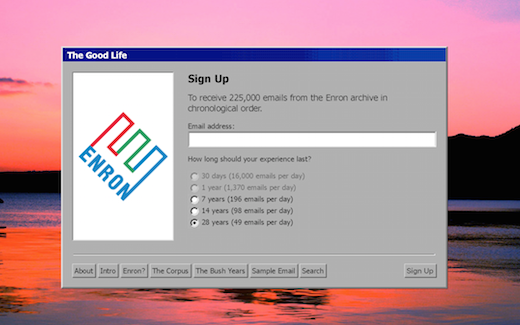

The Good Life delivers 225,000 emails to your inbox after signing up, with options to receive emails spaced out over seven years, 14 years, or 28 years, and Brain and Lavigne also developed a search engine of the archive. “As the Enron emails intertwine with your own, they create an augmented reality experience in your inbox, merging the early 2000s with today,” Brain mused.

A screenshot of the sign up page to receive emails from the Enron archive

“Machine learning systems make decisions based on statistics rather than explicit instructions from human programmer, but these systems are only as good as the data you give them,” Brain explained, alluding to one of the evening’s discussion topics on dataset bias. “While the archive was assumed to be representative of how people communicated, it wasn’t really representative of the general population.” Lavigne added that, now, Google and Facebook have much greater datasets from their users for machine learning purposes.

During the panel, Crawford noted the archive’s application to our current data usage today. “It’s a type of information infrastructure that undergirds so many of the things happening on your phone right now. It was used in labs over and over again, with counterterrorism and fraud detection cases. Even now, a lot of workplace surveillance tools have been trained on the Enron data archive — a giant collection of employee emails is now being used to surveil more employees,” she said.

Lavigne shared that while their project offers a chilling re-enactment of the collapse of a corporation, it also confounds the information gathered about you by machines. “It makes it impossible for your email provider to use your email as accurate data, and obfuscates your email provider’s machine learning model of you.”

Camila Ryder

Graduate School of Arts and Science

Master of Arts in English Literature, Class of 2018